People matters – Why quantifying inclusion is key to climate adaptation

Climate change is expected to have major consequences for the availability and quality of water, and lead to more intense and frequent natural disasters. The impact on people with little capacity to adapt will be disastrous. The CAS side-event ‘For people’s sake’ showed that inclusiveness is essential in climate change adaptation investments to establishing a more equal society. The importance of social inclusion is increasingly acknowledged, but making the concept tangible in the field is considered challenging.

We argue that an adequate representation of the different groups in society requires quantifying the distributional impact of climate change and climate adaptation solutions. This can be done by asking four principal questions. In this way we can give a voice to people affected and let them be part to the solutions.

Social inclusion is central to climate adaptation

Climate change – like all global crises – exposes inequalities in our societies. Different groups in society have different levels of exposure and vulnerability to extreme events. For example, in Bangladesh, the men-women ratio for the mortality rate as a result of cyclone-induced flooding from Cyclone Gorky was 14:1, whereas 75% of the casualties of Hurricane Katrina were over 60 years old.

The large budgets committed to climate action offer an important opportunity to increase resilience to climate change around the world, despite the financial gaps that are still in place. However, as argued by many, climate change adaptation must be done right to ensure long-term effectiveness and impact. When differences in impact (distributional impact) are not recognised or included, there is a tendency to favour areas where the financial benefit is highest, with greater inequality as a result. Maladaptation could make groups even more vulnerable to climate change or redistribute vulnerability between different groups (Schipper, 2020). Examples are:

- Large irrigation schemes that affect water availability in river basins, depriving downstream communities of water and redistributing vulnerability between groups.

- Large dikes provide flood protection but can negatively affect delta ecosystems and related livelihoods.

- Storm-surge barriers can obstruct access to sea for fishing and, in some situations, dikes and barriers can actually exacerbate flood risks if more people start to live in areas that are thought to be safe even though those areas are still prone to extreme events.

A failure to consider the distribution of these effects in society can lead to more impoverishment and inequality. The effects may delegitimise authorities and people may block project implementation or destroy new infrastructure. Further escalation can also result in social unrest and conflict. Addressing social inclusion is therefore not only ethical and socially responsible, it is also relevant to ensure effective climate adaptation and stability. It is therefore crucial for adaptation plans and actions to take the context of the location or group of people into consideration and address social inclusion.

Unpacking the complexity

While the importance of social inclusion is increasingly acknowledged, making the concept tangible in the field is considered challenging. Who should be involved, when or in what way? In the past, we have seen that, in addition to the active involvement of stakeholder groups, more effort is needed to achieve social inclusion. Here, we argue that the quantification of the distributional impact of climate change and climate adaptation strategies is essential to improve social inclusion in climate adaptation.

We suggest that this can be done by asking four principal questions, which can be answered with data and analysis tools, ranging from simple to more advanced forms. The engagement of different groups is vital in the process of quantifying impact. Methods such as multi-stakeholder interaction, dialogue, social learning and collaborative modelling (Basco-Carrera et al., 2017) can be used to engage with different groups.

What are the potentially affected groups and where do they live?

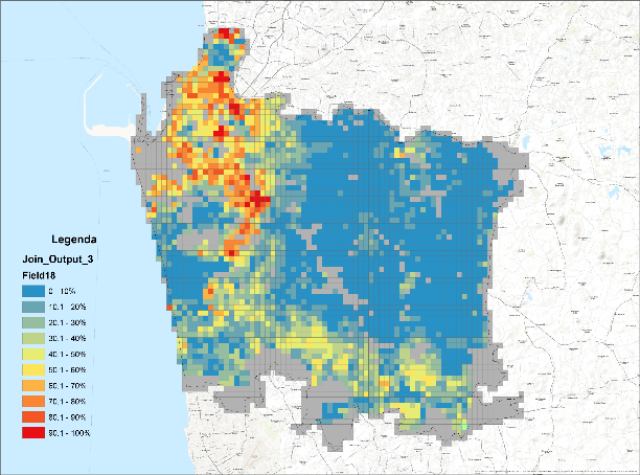

After a general assessment of the climate hazard and the impact of the adaptation measure on the hazard, this question can be answered by using existing maps and asking local experts and communities to identify the exposed communities. Alternatively, or in addition, different groups can be identified by combining open-source spatial data, local census data and machine learning. In the city of Colombo, the socio-economic status of households was mapped using machine learning and combined with flood risk modelling to identify flood risks for different socio-economic groups.

How will lives be affected?

This question can be answered by determining how different groups depend on assets and services that are affected by climate change or adaptation strategies. Stakeholder sessions and interviews focusing on the impact of climate risks, in combination with regular enquiries about whether the impact will be the same for all people, will help identify additional groups and sub-groups.

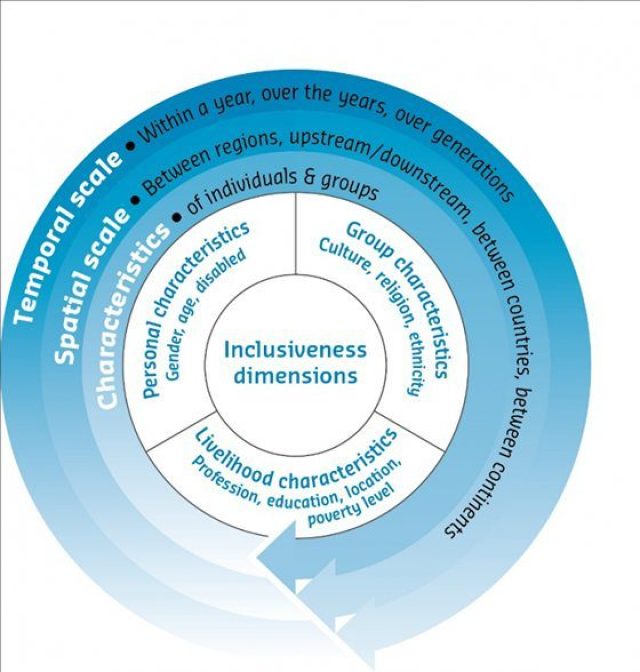

Differences in impact can be related to personal characteristics (such as gender), group characteristics (such as cultural background) or livelihood characteristics (such as type of employment) (see Figure 2). Impact variation was assessed by Cavalcanti (2020), who evaluated the impact of water shortages on water users in different social classes in Sao Paulo on the basis of the social vulnerability index, the marginal utility of water and data analysis.

How will people respond?

People will not simply accept the disasters that overcome them. They will act: by fleeing, protecting themselves, changing their livelihoods, asking for help, or destroying infrastructural measures thought to be causing their loss of livelihood. This capacity to cope with climate change, with or without government interventions, will vary across groups.

To understand the long-term impacts, it is important to look beyond the initial effects and consider the motivation and ability of different social groups to act. Agent-based models which structure and simulate actors’ decision rules can be useful here, as can be seen in, for example, Haer et al. (2020) or Wens et al. (2020).

How are different groups affected in the short and long terms?

Using the answers to questions 1 to 3, a spatially distributed climate change and climate adaptation assessment, for example of flood hazards, droughts, or water availability, can now be stated in terms of the impact on each identified group: a distributional impact assessment. Different groups may be affected differently over time, and so the distributional impact assessment can be conducted for different time scales.

It is important that the quantified impacts should be understood, acknowledged and accepted by the people affected since it is their perspectives that are being represented. In addition to quantifying impacts, including during the evaluation of projects as in cost-benefit analyses, differences between groups can be considered. Kind (2019) demonstrated that, particularly in the case of non-catastrophic risks, the social welfare values of risks are relatively high for vulnerable low-income households, a factor that could be considered in CBAs using equity weighting.

As demonstrated by Kind (2016), distributional impact assessment has the potential to change policy decisions. The voice of the people should therefore be included in these quantification efforts. In past projects, we have seen that a clearer understanding of the impacts on different groups can lead, for example, to a decision not to proceed with the forced relocation of local residents. However, still there is a need for more showcases that help to unpack the complexity.

The mainstreaming of socially inclusive methods shapes equality for the world of tomorrow

Many initiatives have been launched in recent years to guide the shaping of socially inclusive projects. To name just a few: the Dutch community of practice on social inclusiveness, the Partners for Resilience toolbox for inclusive resilience, the Principles for locally led climate adaptation (GCA, 2021), World Bank guidelines and publications such as Unbreakable: Building the Resilience of the Poor in the Face of Natural Disasters (Hallegatte et al., 2017). The growing number of initiatives and publications is proof of the increasing importance of the field. However, distributional impact assessment is not common practice yet.

Decision-makers and financers have a role to play: they can ask for the specification of distributional impacts, and for final decisions to consider impacts on different groups better. We need to keep social inclusion on the agenda of global climate adaptation, to explore and define approaches and tools, solutions and pathways for improving social inclusion in water climate adaptation. The inspiration and experience we have found from our work will get us closer to making this happen. The next step is to integrate the quantification of social inclusion in new and ongoing projects. Join us in our journey to quantify the distributional impact of climate adaptation solution and let us share our experiences.

See also publication: Deltares, NCFR and Southern Cross University, 2019. Social inclusiveness in floods and droughts, How social variations in impacts and responses can be taken into account, working paper.

This blog post is written by Femke Schasfoort, Stephanie Janssen, Audrey Legat, Karen Meijer and Camilo Benitez Avila.

References

- Basco-Carrera, L., Warren, A., van Beek, E., Jonoski, A., Giardino, G., 2017. Collaborative modelling or participatory modelling? A framework for water resources management. Environmental Modelling and Software 91, pp 95-110

- Cavalcanti, V.M., 2020. Differentiating the impacts of water shortages on different social classes of domestic users: A case study of the metropolitan region of Sao Paulo. Master Thesis VU University and Deltares.

- Deltares, 2020a. Flood risk management study in the city of Colombo, using socio-economic status of groups. Not yet published

- Deltares, 2020b. Agent-based model to assess the socio-economic impact of pumped drainage in a Polder 2 in Bangladesh. Not yet published

- Global commission on adaptation, 2021. Principles for Locally Led Adaptation Action Statement for Endorsement.

- Haer, T., Husby, T.G., Botzen, W.J.W., Aerts, J.C.J.H., 2020. The safe development paradox: An agent-based model for flood risk under climate change in the European Union. Global Environmental Change 60, 1-12. [102009].

- Hallegatte, S., Vogt-Schilb, A., Bangalore, M., & Rozenberg, J. (2016). Unbreakable: building the resilience of the poor in the face of natural disasters. World Bank Publications.

- Kind, J., Botzen, W.J.W., Aerts, J.C.J.H., Accounting for risk aversion, income distribution and social welfare in cost-benefit analysis for flood risk management. WIREs Clim Change 2016, e446. doi: 10.1002/wcc.446

- Kind, J., Botzen, W.J.W., Aerts, J.C.J.H., 2019. Social vulnerability in cost-benefit analysis for flood risk management. Water and climate risk, environmental economics 25-2, p 115-134. DOI: 10.1017/S1355770X19000275

- Schipper, E.L.F., 2020. Maladaptation: When adaptation to climate change goes very wrong. One earth 3-4, pp 409-414.

- Wens, M., Veldkamp, T.I.E., Mwangi, M., Johnson, J.M., Lasage, R., Haer., Aerts, J.C.J.H., 2020. Simulating small-scale agricultural adaptation decisions in response to drought risk: An empirical agent-based model for semi-arid Kenya. Frontiers in water 2:15.